How do I suggest coaching for a co-worker?

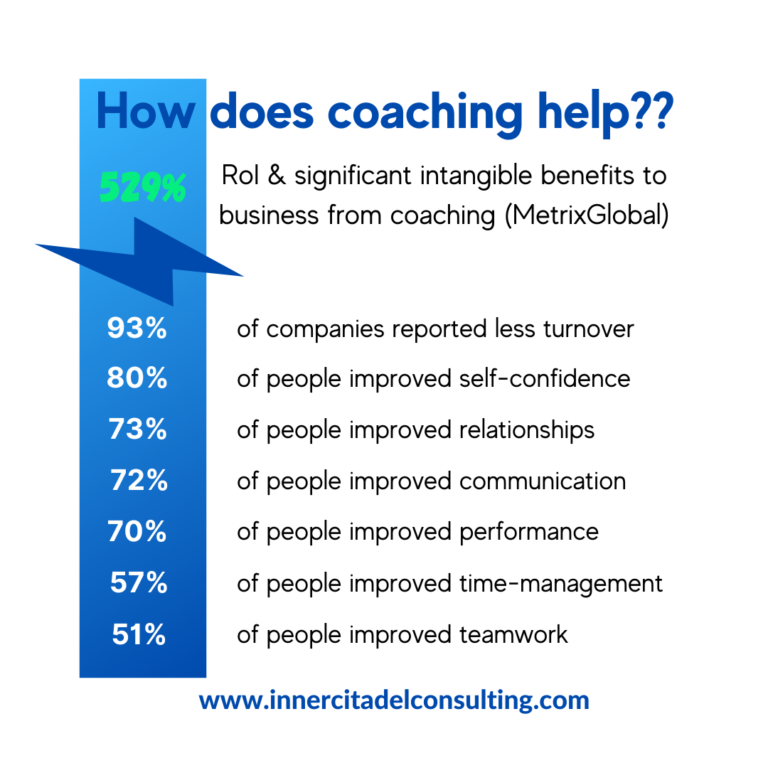

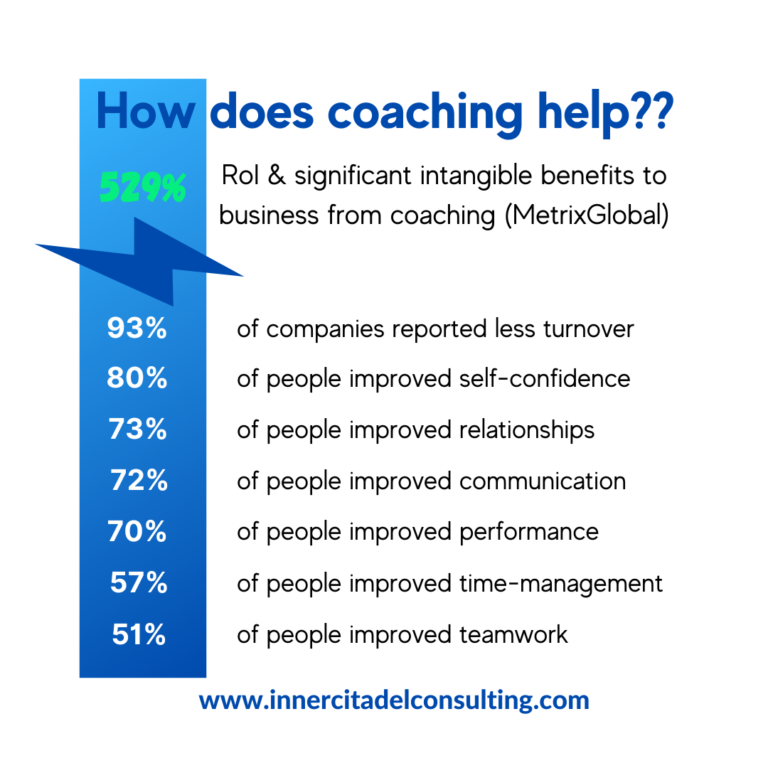

Coaching is a power-boost, not a punishment These days, in some organizations, executive coaching is a normal thing and often expected for most senior leaders. In these kinds of

Coaching is a power-boost, not a punishment These days, in some organizations, executive coaching is a normal thing and often expected for most senior leaders. In these kinds of

Last week I talked about the difficulty of explaining the work of facilitation at networking events, and focused on multi-partial facilitation (or Inter-group Dialogue). Part of the difficulty at

I was at two fantastic business events this week, both celebrations of a sort that were also networking opportunities. I find networking opportunities quite difficult. I know that I

Have you ever seen that video of a horse and rider galloping over a hill, first with upbeat and energetic music and then with ominous, gloomy music? Emotional Culture

Fall Update September has rolled around in a hurry, and it feels like time to check in with you all. I hope your summer has been peaceful and productive.

The direct positive correlation between high team emotional intelligence and high task performance has been firmly established now for at least 5 years. Have you thought about why that

Twenty years ago… Twenty years ago Quintus Jett and Jennifer George of Rice University published a very important article in the Academy of Management Review (AMR was a top

I once asked one of my teachers how I could be more disciplined about getting up a 4am to practice and work out. He said, “Feet on floor –

What does success look like in the coaching space? Feel like? There are some obvious, more or less clinical answers. For example, success looks like a client meeting their

In Part 1 of this series, we looked at how Stoics understood authenticity through purpose. This was *very* high level (or foundational depending on your point of view) and